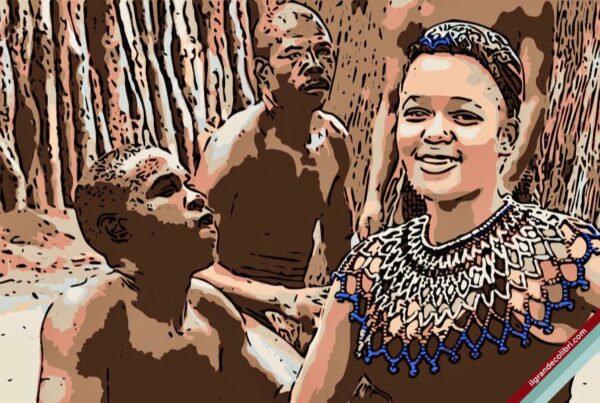

For many homosexual, bisexual and transgender people discrimination begins as soon as their characteristics and inclinations manifest themselves, but for some intersex people it can start at birth. An informal research launched in 2015 by Tunchi Theriso in South Africa (the alias of an intersex rights activist in the rural areas of the Northwest Province) has unfortunately brought to light a terrible widespread practice: children born with anatomical and physiological features that are not unequivocally masculine or feminine are strangled, or killed in other ways, because it’s considered a bad omen.

A Sign of Misfortune

This sad fate, which intersex share with albino children, is the result of popular beliefs that are slowly disappearing, but which are still very strong in the country and especially in less urbanized areas. The “indefiniteness” of the child’s genitals is considered a manifestation of sorcery, a curse, a punishment from God or a sign that the ancestors are angry with their descendants for some reason. This type of infanticide has never been addressed by official research and, in any case, in the small rural communities where this often happens, they tend to avoid the subject – even within themselves.

The paradox, according to David Segal, a pediatric endocrinologist at the Johannesburg hospital, is that the rate of intersex births in South Africa is one of the highest in the world, with one in every thousand children. And since the use of traditional healers as midwives involve 70% of the population, the fate of these lives is in the hands of those who can teach that being intersex is just a less frequent variant, that has no reason to be eliminated.

Killed in Silence

In the forefront, trying to change people’s prejudices, is the LEGBO Northern Cape along with other non-governmental organizations working for the rights of intersex people. Shaine Griqua, the director of LEGBO, tells to the Mail & Guardian how the group stumbled upon this tragedy in 2008 and decided to interview many of the central people involved in this situation. Eighty-eight of the ninety traditional healers, obstetricians and midwives interviewed admitted they practiced this form of selection, always keeping in the dark the mothers who are usually told that the baby was born dead.

The testaments collected are so dreadful that it’s really difficult to even think about it. Griqua fosters the hope that the future will end these kind of crimes: “The pace of change is really slow, but since we probe this research, things have changed and continue to change.”

Signs of Hope

Last October, an international conference called: “Intersex rights in rural areas”, organized by Iranti (meaning “Memory” in Yoruba) in collaboration with Intersex South Africa and with the Commission for the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Cultural, Religious and Linguistic Communities, was attended by many activists, government representatives , community health workers, and traditional healers. Joshua Sehoole of Iranti explains the healers have admitted to be aware of these practices and are committed to reporting them whenever they learn of new infanticides.

Meanwhile, the Health Department and the Society of Midwives of South Africa strongly condemned this practice. It may seem like a small thing, but it is the beginning of a journey that may save the lives of thousands of children and the suffering that their elimination entails.

Michele Benini

translation by Barbara Burgio

©2018 Il Grande Colibrì

Leggi anche: